Are we running out of time?

📚 The definition of time, the sanctity of knowledge, & book burnings as a temporal reference

Listen to a version of this column on the Poetry in Eden podcast, episode #29, available on Spotify or Apple podcasts.

With rising readership and open rates, please continue engaging here on the Substack platform with direct likes and comments. This helps me more than you know.

⏰ The Egalitarian Dream of the Library ⏰

I remember the first time I heard Irma Thomas’s “Time Is On My Side.” I must have been 7 or 8 years old. As the melody washed over me, I closed my eyes and swayed, letting it take hold of me. I placed my small hands over my heart and smiled, captivated by the triumphant lead vocals and the choir that, somehow, carried an undercurrent of sadness. . .What is time? I thought.

Time is one of the fundamental quantities used to describe the sequence and duration of events, as well as their connection to changes in the physical state of a system.

In the International System of Units (SI), time is measured in seconds, with a second precisely defined by the vibrational frequency of cesium atoms in atomic clocks.

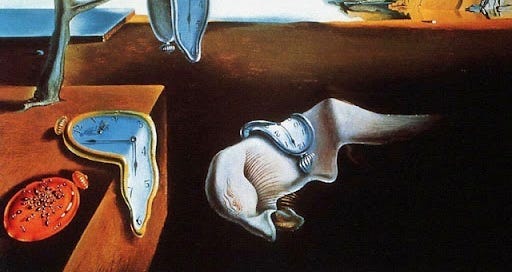

Far from being just a passive backdrop for events, time is dynamic—woven into the very fabric of reality. It can bend and stretch, shaped by motion, gravity, and perhaps even phenomena we have yet to discover.

Time also has a direction, known as the arrow of time. As time moves forward, entropy—our measure of chaos—steadily increases. And while we experience time as a flow from past to present to future, physics suggests that all events, past, present, and future, may coexist within a static, four-dimensional spacetime.

Lately, I find myself thinking more and more about time. Just this morning, I stayed in bed an extra fifteen minutes, yet it felt like an hour. Some days, time races by. And with every passing year, compared to the slow, measured days of my youth, I feel convinced that time moves faster now—never slower.

A few weeks ago, in “Can We Coexist?,” prior to the results of the recent USA presidential election, I asked a direct question to you dear readers:

“The healthcare system in America has been broken for decades. But honestly, name one system in America that is successfully working for the benefit of most citizens and residents, and I’ll write you 5 personal poems.”

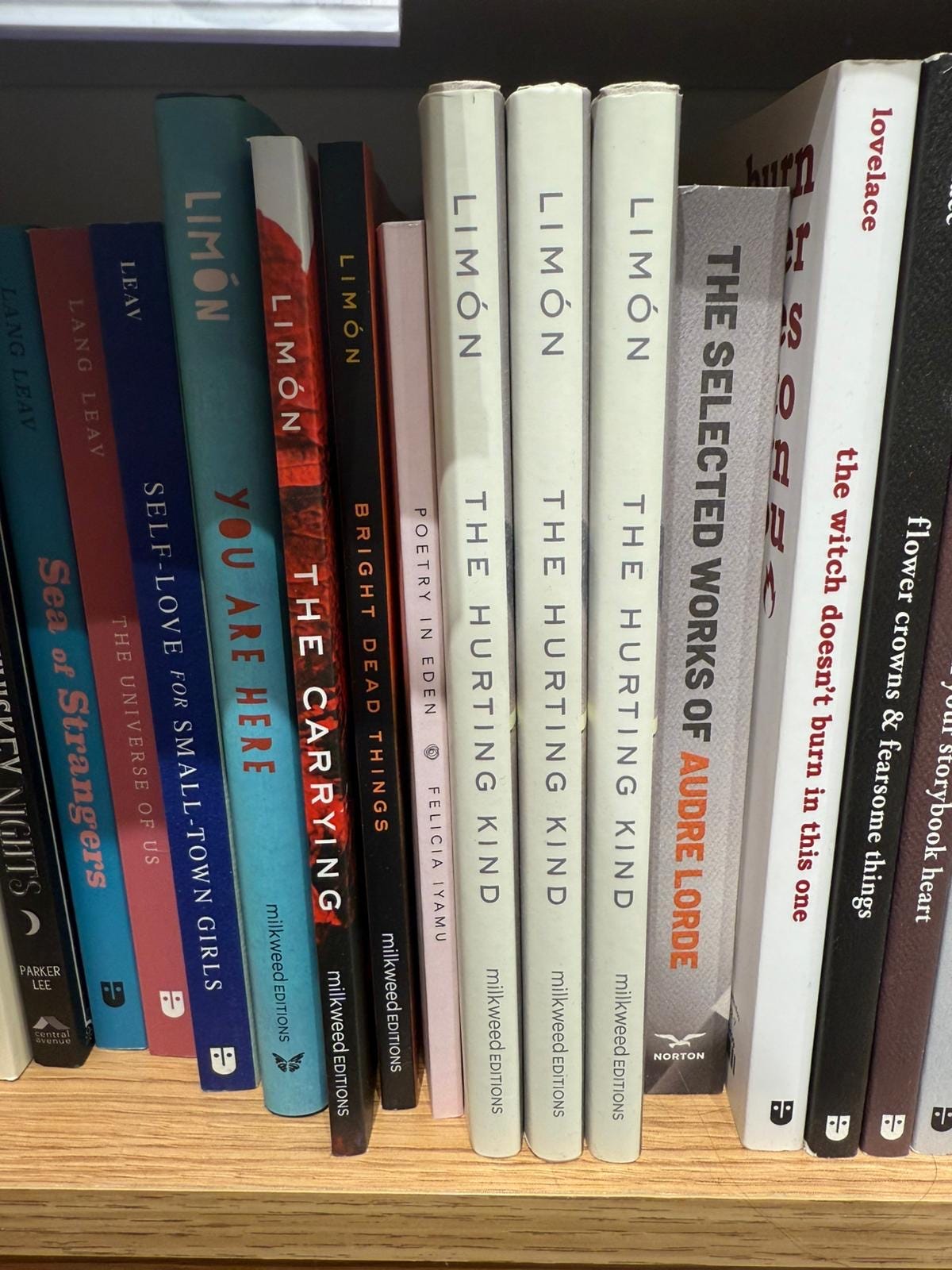

Unfortunately, my reflections on American systems did not lead to any clear answers. But just a few days later, a dear friend sent me a photo—a snapshot of my book on the shelves at Barnes & Noble in Manhattan—a literal dream come true.

The image reminded me of the library from my childhood, a place where time seemed to stand still, yet offered endless possibilities.

I wrote much of my first book—complete at over 330 pages—within the walls of the New York Public Library. Their computers have Microsoft Word, and at the time, I was not ready to purchase the full suite for my desktop.

Once I received my beautiful cobalt blue library card, I set out to explore and discover which of the city’s gorgeous libraries would become my favorite. To this day, I say that every library between 14th Street and Central Park South is my favorite. Each has its own charm and its own quiet magic.

After a few visits, I learned to come prepared—to wear a scarf and my favorite perfume. Often, I was seated next to a homeless person who was using the public computers with evident joy. The smells could be overwhelming, but I’d smile, appreciating what it meant to be part of an equal-access space.

🎙 NEW: Listen to the “Poetry in Eden” podcast on Spotify or Apple podcasts. Episode #29 is a version of this week’s column.

Wow, I thought to myself. I can sit here and use this beautiful library, and so can they! This is what I always dreamed America could be—a place where everyone has some dignity and access, regardless of their circumstances.

In the library, anyone can enjoy what it has to offer. There are time limits on computer use to ensure fairness, and the shelves stretch endlessly with books of every kind. Books are knowledge, and knowledge is power!

Books are far more than bound pages—they are vessels of knowledge, the essence of human progress. Throughout history, they have preserved ideas, inspired innovation, and connected generations. Education, the foundation of societal growth, begins with books. Yet, this immense power has often made them targets for control and censorship, as governments and institutions seek to shape ideology and suppress dissent.

In 1953, Ray Bradbury published Fahrenheit 451, a novel that explores the dangers of censorship, conformity, and the erasure of knowledge. It highlights the critical importance of independent thought, the preservation of ideas, and the fight against apathy and authoritarian control.

In the novel’s dystopian society, books are outlawed, leading to a populace steeped in ignorance and dominated by state-imposed control. Fahrenheit 451 became a critical success, cementing itself as one of the most iconic and influential works in American literature. Ironically, it faced real-world censorship in apartheid South Africa and in several schools across the United States.

Bradbury insists:

“You must lurk in libraries and climb the stacks like ladders to sniff books like perfumes and wear books like hats upon your crazy heads. . .may you be in love every day for the next 20,000 days. And out of that love, remake a world.”

Incredible—20,000 days amounts to 54 years, 9 months, and 20 days. In that time, with plans to colonize Mars instead of addressing climate change, with efforts to exterminate holy and indigenous peoples instead of respecting sacred lands, and with the relentless drive to bolster capitalism and exploitation, it is hard to imagine what our world might look like in 20,000 days.

It makes me wonder sometimes: are we running out of time? And if we are, what can we do about it?

🔥 Beware the Burning of Books 🔥

As Donald Trump returns to the presidency, his critical perspective on the U.S. Department of Education—the smallest of all Cabinet agencies—brings renewed attention to the ongoing debate over government control of education and the America he plans to remake. Trump expressed concerns about curriculum content, particularly topics he viewed as overly critical of American history or promoting certain ideologies.

To address these concerns during his 2017-2021 presidential term, Trump promoted the idea of “patriotic education” through initiatives like the 1776 Commission/Report. The commission aimed to emphasize traditional American values in schools, presenting a perspective of U.S. history that highlighted national achievements while downplaying systemic issues such as slavery and racism, which are seen as “radicalized view(s) of American history” which “vilified [the United States'] Founders and [its] founding.”

Although the Report resonated with supporters who valued limited federal involvement and expanded parental choice, many historians and educators criticized the 1776 Report for being politically motivated and historically inaccurate, pointing out that it ignored the complexities of U.S. history, lacked input from professional scholars, and sought to minimize uncomfortable truths about inequality and injustice.

A politically motivated and historically inaccurate education system? These controversies surrounding education and curriculum are part of a long historical pattern where governments have sought to control knowledge and shape ideology, often leading to the destruction of books and intellectual heritage. Bradbury wrote:

“With schools turning out more runners, jumpers, racers, tinkerers, grabbers, snatchers, fliers, and swimmers instead of examiners, critics, knowers, and imaginative creators, the word 'intellectual,' of course, became the swear word it deserved to be.”

One of the earliest recorded instances of book destruction occurred during the reign of Emperor Qin Shi Huang in China (213–210 BCE). To consolidate power and establish Legalism as the state ideology, Qin ordered the burning of books that contradicted his policies, particularly Confucian texts.

The 20th century saw some of the most infamous instances of book burning. In 1933, Nazi Germany orchestrated mass burnings of books by Jewish, socialist, communist, and “un-German” authors, targeting works by intellectuals like Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and Karl Marx. These burnings were part of a broader effort to align education and culture with Nazi ideology.

During Donald Trump's previous presidency (2017-2021), several books faced widespread bans, censorship, or restrictions in various contexts—whether at schools, libraries, or public spaces. Books like: “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates; “Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You” by Jason Reynolds; “I Can’t Breathe: A Killing on Bay Street” by Matt Taibbi; “The 1619 Project” by Nikole Hannah-Jones, and more.

What do these banned books all have in common? They discuss and dissect the history of slavery and race relations in America. Bradbury writes:

“There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches. . .You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.”

🕊 “Peace, Montag” 🕊

In every instance, the destruction and censorship of books has represented the symbolic and practical method of erasing opposing ideas, destroying the very foundations of education, culture, and intellectual freedom.

As we reflect on these historical examples and the ongoing debates over education in contemporary politics, it becomes clear that the battle on knowledge is far from over. . .it has just begun. Books remain a powerful tool for preserving and sharing ideas. The struggle for control over education underscores the enduring importance of knowledge as a force for both liberation and oppression–a theme Bradbury was also inspired by in 1953:

“If you don't want a man unhappy politically, don't give him two sides to a question to worry him; give him one. Better yet, give him none. Let him forget there is such a thing as war. . .Peace, Montag. Give the people contests they win by remembering the words to more popular songs or the names of state capitals or how much corn Iowa grew last year. Cram them full of noncombustible data. . .Then they'll feel they're thinking, they'll get a sense of motion without moving. And they'll be happy, because facts of that sort don't change.”

With this foresight, we can get ahead of the censorship soon to come and maybe remake a world based in love. In defending the integrity of education and the preservation of books, we may uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and progress that have driven human advancement for centuries.

Personally, I do not think we are running out of time—not yet. But when we begin to see the “burning of books,” I urge us to ask this question again, and this time, with urgency.

The poem of the week is unpublished and will be in an upcoming book. So, hence the paywall. It is available to premium subscribers only.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poetry in Eden to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.